Do you feel a sense of responsibility when you realize that, when you read the Great Books, you are dealing with some of the most profound and influential documents in the history of the world? I think that some people actively avoid that responsibility. Like the scriptures, albeit to a lesser extent, the Great Books will change you, and many people don’t want to be changed.

Here are the readings for the upcoming week:

- The Aeneid of Virgil, Book III (GBWW Vol. 12, pp. 119-136)

- History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, Book III (GBWW Vol. 5, pp. 447-481)

- Experience and Education by John Dewey, Ch. 3 (GBWW Vol. 55, pp. 104-111)

- Riders to the Sea by John M. Synge (GGB Vol. 4, pp. 342-352)

- “Numerical Laws and the Use of Mathematics in Science” by Norman Robert Campbell (GGB Vol. 9, pp. 222-238; Chapter VII of What Is Science?)

- The City of God by St. Augustine, Book IV (GBWW Vol. 16, pp. 249; in the linked text, it’s the material under the heading “The empire was given to Rome . . .” and its subheads)

We have three 20th-century pieces again this week; I feel so modern and up-to-date!

Here are some observations from last week’s readings:

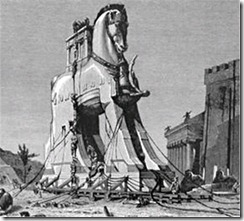

The Aeneid of Virgil, Book II: Beware of Greeks bearing gifts! The Trojans got played like a fiddle, being persuaded to take the giant horse inside the city. What a heel Aeneas was to leave his wife behind in the flight from Troy’s destruction. I suppose she had to be removed to set up the love affair with Dido. And poor Priam’s death was pathetic; first he has to watch the death of his son and then he himself is killed.

The Aeneid of Virgil, Book II: Beware of Greeks bearing gifts! The Trojans got played like a fiddle, being persuaded to take the giant horse inside the city. What a heel Aeneas was to leave his wife behind in the flight from Troy’s destruction. I suppose she had to be removed to set up the love affair with Dido. And poor Priam’s death was pathetic; first he has to watch the death of his son and then he himself is killed.- History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, Book III: The debates over the fates of Mytilene and Plataea were very unsettling. “Should we kill everyone in Mytilene, or only around 1,000 of them? No consideration of justice will enter into our calculations. We’re only concerned with what’s in our interest.” I hope the irony of this Athenian debate’s following on the heels of Pericles’s funeral oration in Book II is evident. And the Spartans were apparently no better, executing out of hand the men of Plataea to gratify the Thebans after the Plataeans had surrendered themselves to Spartan justice.

- Experience and Education by John Dewey, Ch. 2: I wonder if we’ll see Dewey owning a connection to Bacon or Hume. Exalting experience in the educational process goes back all the way to Aristotle in some ways. Dewey’s warnings about “educational reactionaries” seem a bit paranoid today. Would that those reactionaries had been more successful.

- “My First Acquaintance with Poets” by William Hazlitt: I learned a lot about Coleridge and a little about Wordsworth from this essay. Russell Kirk pointed to Coleridge as an important figure in conservative thought. Could he have been thought so in 1798, a Unitarian minister rebelling against the poetic conventions of the previous two centuries? It’s a little disheartening to know that Wordsworth and Coleridge wrote their poems in ordinary, everyday English, but that 21st-century students often can’t understand them.

- “Measurement” by Norman Robert Campbell: This piece resonated more with me than it would have if I hadn’t read Euclid last year. I remember commenting on the difficulty of working through many of his ideas without recourse to the numerals we take for granted. Campbell asks us to think through what it means to count and measure and what standard is appropriate to use. I’m not sure I followed him all the way through the section on density.

- The City of God by St. Augustine, Book III: I’m trying to imagine how a 5th-century pagan would have attempted to answer Augustine’s argument in this book, and I can’t come up with any coherent line of counterargument. I can only imagine the pagan left stewing in his own juice. Augustine simply uses authoritative pagan authors to demonstrate that Roman history had always been plagued by crises and wars going back centuries before Christ. It made no sense to blame 5th-century problems on the abandoning of the worship of gods that had never prevented those kinds of calamities even in the days when their preeminence was undisputed.

After the stress of organizing and hosting an academic conference last week (with lots of help from others), I’m hopeful that this week will be a little more relaxed. That’s not to say I don’t still have more things to do than I can possibly finish, but at least I won’t have certain kinds of deadlines staring me in the face. I hope you’ll find the time to read this week and let me know how your own efforts in that area are proceeding.

Didn’t Aeneas lose his wife in the chaos of war and then get visited by her ghost? The ghost told him to move on because the gods need him to marry into the royal house of the Latins. Anyways, I’m wondering if this mitigates his heelhood.

Many religions have thought the past was better than life under the latest modern ideas. Some have even blamed earthquakes, hurricanes, etc. on a perceived increased in wickedness. Augustine’s argument probably applies in these cases as well.

Stan, see my reply to Mom’s comment on Aeneas. Re: Augustine, I’ll be the first to say that some eras excel in virtue more than others do. Augustine points to all sorts of disasters and catastrophes that occurred before the coming of Christ, in the “Golden Age” the pagans were yearning for, and asks, “Do you want to blame those on us, too?” It’s really quite clever.

What do you mean, calling Aeneas a heel? He did just what he was supposed to do as a great hero in Troy. He had had daddy on his back and his son by the hand. Dutiful wife was following right behind. How many people could you hold on to as you exit a burning city!

Your translation might be more charitable to Aeneas than mine (C. Day Lewis). Aeneas says that as they were leaving the city, he heard footsteps and panicked. He never looked back for his wife nor gave her a thought until they had reached the rendezvous point. And this after he had fought so bravely earlier the same night. So yes, I think this is a bad moment for him.